Welcome to another edition of the Talk to the Vet weekly column, where we bring you, our esteemed farmers, up to date with all things animal healthcare- related. Today, we will look into the interesting world of veterinary parasitology.

Simply put, veterinary parasitology is a branch of veterinary medicine that deals with the study of morphology, life cycle, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and control of eukaryotic invertebrates that depend upon other invertebrates and higher vertebrates for their propagation, nutrition and metabolism without necessarily causing the death of their hosts

But we will specifically look at Echinococcosis or hydatid disease, an infection caused by tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus, which is a tiny tapeworm just a few millimetres long.

Five species of Echinococcus have been identified, which infect a wide range of domestic and wild animals.

Echinococcosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease that is transmitted by carnivorous definitive hosts harbouring the intestinal worm stage. It affects domestic livestock, wild herbivorous and omnivorous mammals as well as humans as intermediate or dead-end hosts, where the cystic metacestodes (larval stages) are present in various internal organs.

The disease symptoms are caused by cysts which are slow growing fluid-filled structures that contain larvae and are most often located in the liver or lungs.

Called hydatid cysts, they act like tumours that can disrupt the function of the organ where they are found, cause poor growth, reduce the production of milk and meat, and rejection of organs at meat inspection.

Echinococcus infection is a disease listed in the World Organisation of Animal Health (WOAH) Terrestrial Animal Health Code, and must be reported by member countries, according to the WOAH Code.

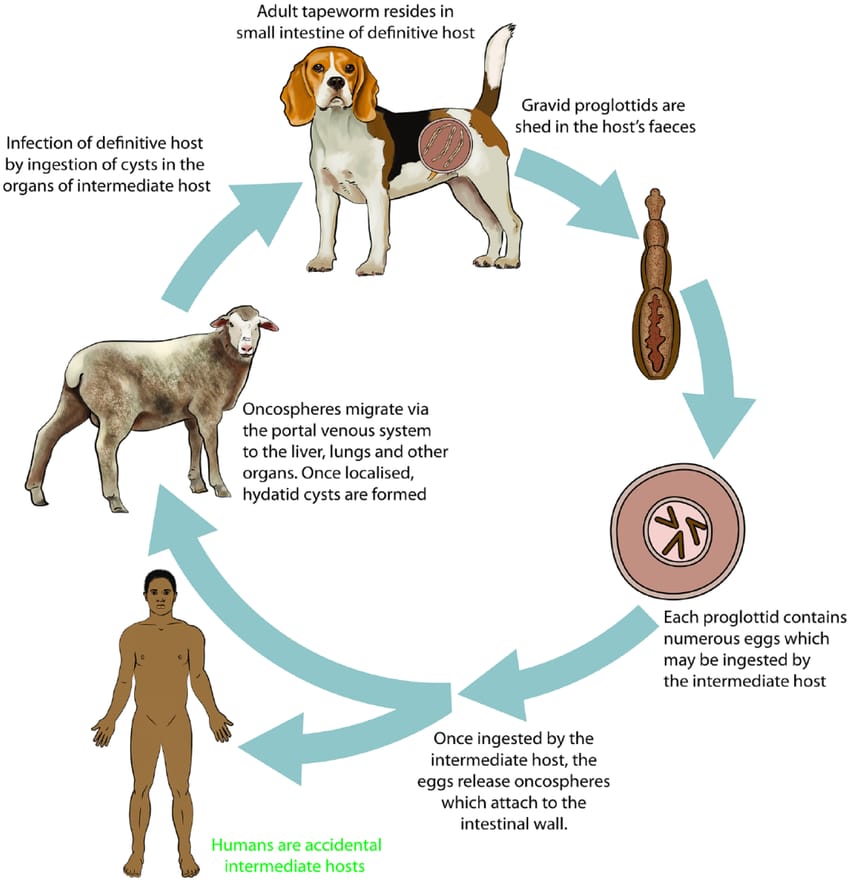

The life cycle

Adult worms live in the small intestine of the definitive host. They reproduce, releasing eggs into the environment in the faeces of the host animal. The eggs are well-adapted to survive in the environment for as long as a year in cool moist conditions, but are susceptible to desiccation.

Fresh eggs are sticky and may adhere to the fur of definitive hosts facilitating their spread. The intermediate host ingests the eggs incidentally while grazing, foraging, or drinking. The eggs hatch in the small intestine, become larvae that penetrate the gut wall, and are carried in the circulatory system to various organs.

The cysts, which contain larvae, either comprise fluid-filled bladders, which contain larval pre-tapeworms (protoscoleces), and cause the disease cystic echinococcos due to a multivesiculated lesion or mass containing protoscoleces that grows rapidly by exogenous budding, and cause alveolar echinococcosis in rodents and other small mammals.

Though slow growing in humans and long-lived animals (e.g. camels or horses) cysts of E. granulosus can reach a size of 10-20 centimetres, but in sheep are usually 2-6 centimetres.

The life cycle is completed when the cysts are ingested by a carnivorous definitive host, the larvae (protoscoleces) are released from the cyst into the small intestine and develop into adult tapeworms that produce eggs, which are released into the environment in the faeces of the host animal within 25-80 days, depending on the species and strain of Echinococcus.

Public health risk

Laboratory workers, animal handlers, veterinarians, dog owners are all at higher risk of infection. Since the eggs are shed in the environment, they can contaminate fruits, vegetables or water, or can stick to the fur of an animal, and be transferred on hands to the mouth.

In humans, the cysts of E. granulosus usually develop in organs such as the liver or lungs, so the signs of disease are due to liver or lung deficiency. Rarely, cysts form in bones causing spontaneous fractures, or in the brain causing neurological signs.

Cysts or lesions of E. multilocularis occur primarily in the liver and grow slowly but with eventual serious liver pathology and a high risk of mortality if untreated. The cysts occasionally rupture and cause severe allergic reactions in humans.

Treatment strategies (chemotherapy, percutaneous radiological techniques, but mainly surgery) predominantly target active disease. Prevention strategies encompass anthelmintic treatment of dogs, slaughter hygiene, surveillance, and health-educational measures.

For Namibia, there are only anecdotal and unpublished records of livestock which, however, seems to occur regularly at least in cattle. Such data are mainly contained in veterinary slaughterhouse records.

According to a study conducted in 2022, this parasite seems to be widespread in wildlife across the country, especially in antelopes, jackals (Canis mesomelas), and lions (Panthera leo).

The source of sheep infection is therefore uncertain: domestic dogs may acquire infection via sheep carcasses or offal, or there may be a spill-over from a wildlife cycle, e.g. via infected jackals defecating on sheep pasture.

In contrast to goats, sheep are rather unusual hosts for E. canadensis, which may indicate that they are not an integral part of the parasite’s lifecycle in Namibia. Domestic pigs, which are important hosts for the G7 genotype in various parts of the world, are only sporadically kept in southern Namibia and are unlikely to play a role in transmission here.

It may be noteworthy that the only human CE case that had ever been reported in Namibia was a 17-year-old boy from a sheep farm, which again highlights our gaps of knowledge on the epidemiology of CE in this country.

*For enquiries or suggestions on any topic that you would want to be covered please reach out at punamuza22@gmail.com or WhatsApp me at +264 81 723 4553.