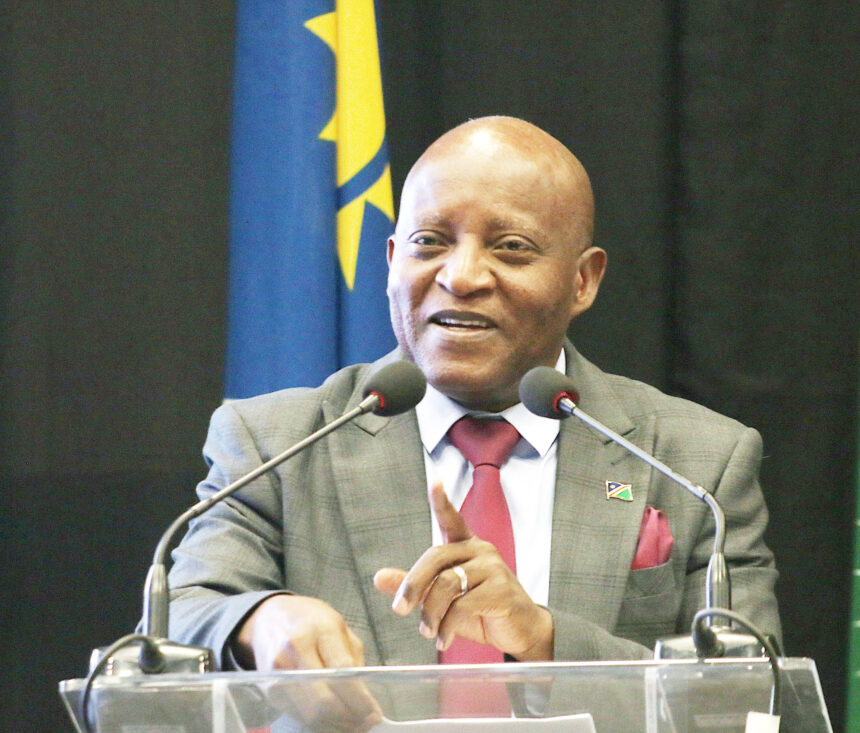

Rudolf Gaiseb

The newly tabled Public Enterprise Governance Amendment Bill gives Prime Minister Elijah Ngurare the overarching administrative authority over all public enterprises.

Ngurare told the parliament last week that these stewardship and performance oversights will be exercised in the “best interest of the state and of each enterprise.”

This power transfer originates from the public enterprise minister designated in the 2019 Act. This was under the Minister of Finance and Public Enterprises, but it was later brought under the Minister of Finance.

Now, instead of being run by a minister, the PM is in charge of these public enterprises, bringing on board “relevant ministers”, each responsible for the public enterprises within their respective ministries.

Ngurare is, however, subject to consulting the Cabinet while performing his powers and functions.

At the same time, the relevant ministers answer to him.

The prime minister will generally control remuneration levels and benefits for employees of public enterprises and the classes of contracts entered into by a public enterprise, including joint ventures, acquisition of other businesses and agreements relating to the corporate structure of a partner of a public enterprise.

In addition, “the relevant minister will represent the State’s ownership interest of the public enterprise, appoint and remove board members, provide strategic directions and leadership to the board, and monitor and evaluate the performance of the public enterprise,” the Bill states.

They will enter into governance and performance agreements with the board and individual board members and approve the integrated strategic business plan, the annual business and financial plan, the annual budget and the investment policy of the public enterprise.

It also includes the approval of dividend policy submissions, consulting the finance minister and presenting the annual report of the public enterprise to the National Assembly.

Meanwhile, executive director of the Institute for Public Policy Research and political analyst Graham Hopwood suggests the bill is an iteration of the Central Governance Agency and the State-Owned Enterprises Governance Council of the early 2000s. These governance models harboured similar challenges to those raised by Ngurare last week.

Initially, under the decentralised model, individual portfolio ministries were solely responsible for all functions related to the public enterprises under their jurisdiction.

Subsequently, under the Dual-Governance model, the responsibilities for monitoring and governing public enterprises were shared between the Portfolio (Shareholder) Ministries and the State-Owned Enterprises Governance Council.

This model was implemented in 2006 and ran until 2015, under the provisions of the State-Owned Enterprise Governance Act. The model did not provide optimal governance.

Despite various changes in governance and the operation of these public enterprises under a hybrid model, Hopwood criticised that “badly managed and loss-making state-owned companies and agencies have proliferated.”

According to the analyst, none of the various “iterations” have been able to enforce basic corporate governance standards, despite some progress regarding commercial public enterprises under the ‘Ministry of Finance and Public Enterprises’ since 2015.

The bone of contention, he suggests, is how this model will move the dial on the poor governance and underwhelming outcomes at many public enterprises.

“The proof will be in how the government plans to change the underlying culture that has allowed mismanagement and corruption to thrive. Perhaps they have found the magic key to unlocking progress,” he added.

Photo: Heather Erdmann