The passing of Namibia’s founding president and revered anti-apartheid icon Sam Nujoma marks the end of an era, both for Namibia and the African continent.

Nujoma, who died in Windhoek on Saturday at the age of 95, was the last of a generation of African revolutionary leaders who freed their countries from colonial bondage to attain independence, at a time when this was politically unfashionable in the global south.

His passing is a clarion reminder that there was indeed a time in Africa when giants walked the earth, and this includes revered personalities such as South Africa’s icon Nelson Mandela, Zimbabwe’s liberator Robert Mugabe, Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda, Mozambique’s Samora Machel and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, among many others.

Nujoma headed Namibia’s liberation struggle as the leader of Swapo between 1960 and 1989, before becoming the country’s first president in 1990 until 2005.

Namibia, then known as South West Africa, suffered decades of looting and colonial violence at the hands of Europeans who had flocked to the country at the turn of the 20th century. It all started with the 1904 uprising against German colonisers, who in turn killed thousands of Namibians in what is now known as the first genocide of the 20th Century.

Apartheid Rule

Namibia was under German occupation from 1884 until 1915 when Germany lost the colony in the first World War. Namibia then fell under the rule of apartheid South Africa, which extended its racist laws to the country, denying black Namibians any political rights, as well as restricting social and economic freedoms.

The introduction of sweeping brutal legislation by the South African apartheid regime culminated into a protracted struggle for independence. The struggle reached its peak in 1966, marshalled by the Nujoma-led Swapo military wing People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) and other like-minded frontline states.

Resistance

Nujoma drew inspiration from the country’s early resistance fighters such as Hendrik Witbooi, Samuel Maharero, Jakob Marengo and many others who fought and stood firm against German occupation of the 1880s.

By 1959, Nujoma had become the head of the Owamboland Peoples Organisation (OPO), the independence movement that was the forerunner to Swapo.

Early Politics

Nujoma became involved in politics in the early 1950s through trade unions. His political outlook was shaped by his work experiences, awareness of the contract labour system, and his increasing knowledge of the growing independence campaigns in many countries across Africa.

Massacre

After the Old Location Massacre on 10 December 1959, Nujoma was arrested and charged for his part in the resistance and faced threats of deportation to the northern part of the country.

By the directive of OPO leadership and in collaboration with Ovaherero chief Hosea Kutako, it was decided that Nujoma join the other Namibians in exile who were lobbying the United Nations for the anti-colonial cause on behalf of Namibia.

To exile

At age 30, Nujoma was forced into exile. With no passport, he adopted different personas and blagged his way onto trains and planes – ending up in Zambia and Tanzania before heading to West Africa.

With the help of Liberian authorities who were early backers of black Namibians’ push for independence, Nujoma flew to New York and continued to petition the UN for Namibia’s independence – but South Africa dug in.

UN Petition

Nujoma was a hated man and was branded a “Marxist terrorist” by the brutal racist South African regime for leading forces that fought alongside other anti-apartheid movements for the country’s independence.

With support from Cuban troops who were fighting in neighbouring Angola, Swapo guerrillas were able to attack South African bases in Namibia from Angola.

Returning from exile, Nujoma was swiftly rearrested by the South African authorities and deported to Zambia six years later.

He led Swapo forces from exile, before returning to the country in 1989, a year after South Africa had agreed to accept Namibia’s independence.

South Africa was becoming more isolated internationally and the cost of military intervention was increasing, which eventually forced the regime to grant Namibia independence in 1990 after almost 25 years of bloody warfare.

Road to freedom

In the late 1970s, Nujoma led the Swapo negotiations team between the Western Contact Group (WCG), which consisted of West Germany, Britain, France, the US and Canada, and South Africa on the one hand, and the Frontline States and Nigeria on the other, about proposals that would eventually become United Nations Security Council Resolution 435, that was passed in September 1978.

Resolution 435

The agreement on Resolution 435, which embodied the plan for free and fair elections in Namibia, had its implementation bogged down for another 10 years.

South African delaying tactics and the decision by American president Ronald Reagan’s administration to link a Cuban withdrawal from Angola to Namibian independence frustrated hopes of an immediate settlement.

On 19 March 1989, the signing of the ceasefire agreement with South Africa took place, which resulted in the implementation of the UN Security Council Resolution 435.

Return

After 29 years in exile, Nujoma returned to Namibia in September 1989 to lead Swapo to victory in the UN-supervised elections that paved the way for the country’s independence.

Nujoma returned a day before the UN deadline for the Namibia people to register to vote for an election that would draft a constitution when it received its independence from South Africa.

The Constituent Assembly, elected in November 1989, chose Nujoma Namibia’s first president and he was sworn in on 21 March 1990, in the presence of Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Secretary-General of the UN, Frederik de Klerk, president of South Africa, and Nelson Mandela, who had just been released from prison.

At independence, Namibia was gravely divided as a result of a century of colonialism, dispossession, and racial discrimination, compounded by armed struggle and propaganda.

Demonised

Swapo had been so demonised by the colonial media and by official pronouncements that most white people, as well as many members of other groups, regarded the movement with the deepest fear, loathing, and suspicion.

One of Nujoma’s earliest achievements was to proclaim the policy of “national reconciliation”, which aimed to improve and harmonise relations among Namibia’s various racial and ethnic groups.

Under his presidency, Namibia made steady economic progress, maintained a democratic system with respect for human rights, observed the rule of law, and worked steadily to eradicate the heritage of apartheid in the interests of developing a non-racial society.

Nujoma successfully united all Namibians into a peaceful, tolerant, and democratic society governed by the rule of law.

Hewasespeciallyconcernedwith the plight of children, introducing maintenance payments obliging absent fathers to contribute to the cost of raising their offspring.

He also championed the advancement of women, helping to change traditional patriarchal practices that forced widows out of the family home once their husband died, and also preserved stability to ensure development efforts were supported by international donors.

Strong views

Despite his commitment to foster racial reconciliation and harmony between the various ethnic groups of Namibia, Nujoma made controversial and strong remarks after his presidency.

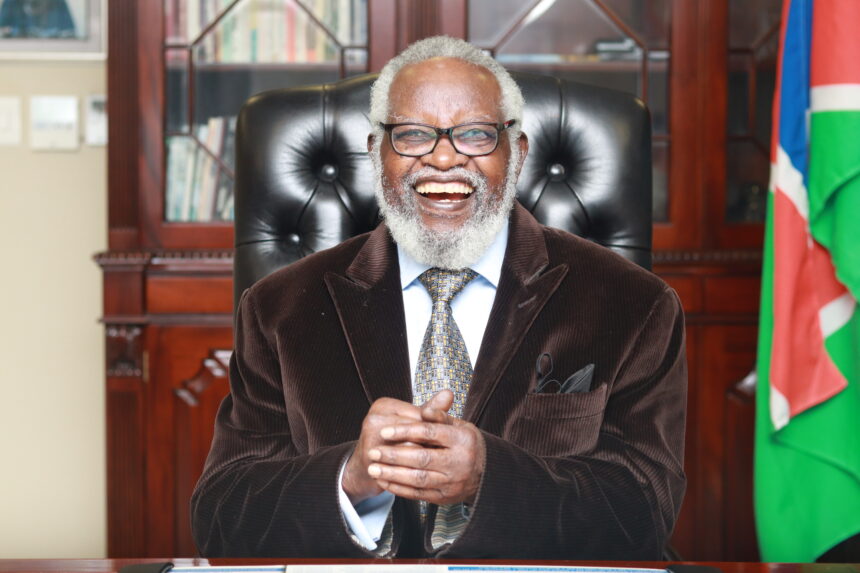

His warm, broad smile and easy-going manner made him likeable and accessible but was never one to be mistaken for weakness. When criticised for his style of government or questioned about his party’s political past, the wide smile could turn sour pointing a finger at whoever dared openly question or criticise him.

In 2009, he called on the Swapo party youth to take up arms and “drive the colonists out of the country

Warning

He would again hog international headlines when he attacked the German-speaking Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (DELK), accusing it of having “collaborated with the enemy before independence and possibly still being an enemy of Namibians”.

He warned the DELK: “We tolerate [them]. But if they don’t behave, we will attack them. And when they call their white friends from Germany, we will shoot them in the head”.

His fierce anti-Western rhetoric also rocked the world when he waged a verbal war on homosexuality, branding it as “foreign and corrupt ideology”. -ohembapu@nepc.com.na