Lahja Nashuuta

Before the war, Oukwandongo was a thriving rural settlement, 35 kilometres south of Outapi. Known for its fertile Omahangu fields, rich grazing land, and cultural ties with neighbouring Angola, the village was once a bustling hub where families lived in peace.

But everything changed during the liberation struggle when South African soldiers took over the village, torching homes, destroying crops, and scattering families. Overnight, the village was reduced to ruins, its people caught in the crossfire of Namibia’s liberation struggle, and houses were left empty.

Because of its dense bush and forest cover, Uukwandongo served as a transit route for many Omusati residents fleeing into exile in Angola. Meanwhile, South African troops used the village to ambush PLAN fighters who were helping villagers cross the border.

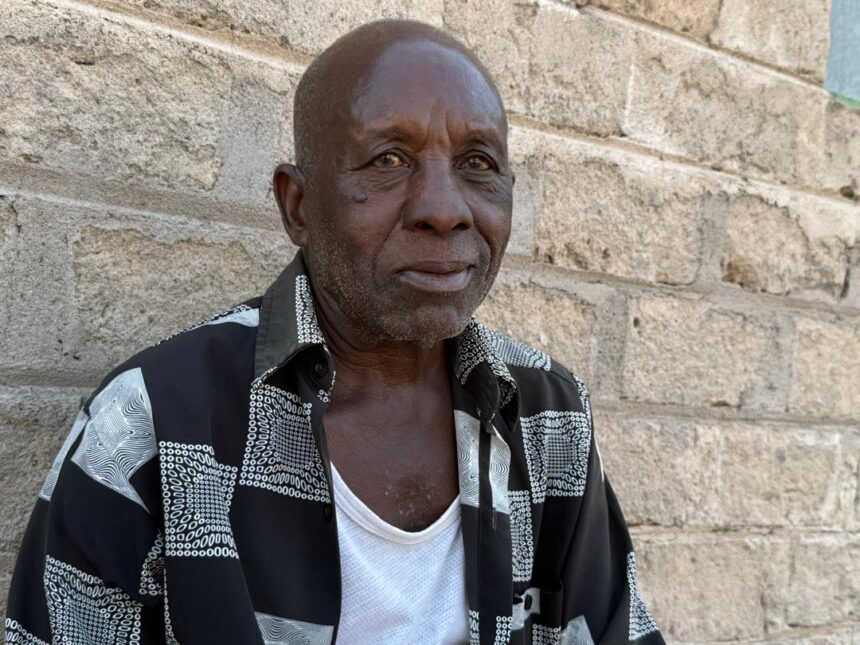

“It was chaotic; we were caught between the two,” recalls Otto Iyambo, the only known survivor of the war who lived to tell the story.

“South African soldiers were after us because they knew most households were hiding and feeding PLAN fighters. At the same time, if the PLAN fighters suspected you had betrayed them, they would also turn against you.

We were caught between the two. Gunshots were everywhere.”

Iyambo, a former teacher at Uukwandongo Combined School and now the village’s deputy headman, shared his memories with New Era on the eve of Heroes Day.

The war veteran described how the war silenced a once-vibrant village, leaving behind ruins, silence, and stray dogs wandering in search of their owners. Burials were a daily ritual.

“This used to be a vibrant village,” he said, his voice thick with longing.

“Before the war, it was crowded with people and cattle. Young men passed through here on their way to Angola for initiation, always traveling at night. People believed that finding their footprints meant good luck. But all of that disappeared when the war came,” he chronicled.

Iyambo admits that he and his wife were involved in the struggle by sheltering fighters.

“I was a trusted Swapo member. Since I was the only one with a car at the time, I helped transport supplies from Outapi for the fighters. When they were injured, they left their uniforms at my house, and I gave them civilian clothes so they could move around without being detected.”

His loyalty came at a price. He was arrested several times, tortured, and interrogated by colonial forces.

“They came to my house almost daily, demanding information. But I never betrayed our soldiers. Even our children were taught how to answer when asked about the so-called ‘terrorists,’ as the South Africans called the fighters,” Iyambo said.

One of his darkest memories is from 1978. “Soldiers stormed the school and drove away teachers and students. People wept, not knowing where their loved ones were taken. Some returned the next day. Many never came back. To this day, their fate remains unknown.

On another occasion, Iyambo, along with his parents and neighbors, was detained and taken to Onavivi in the Omusati region, where they were brutally electrocuted and beaten.

“One of my neighbours died there… We were not allowed to work at night. At sunset, we made sure to dim the fire so it would not draw attention. In the early morning, we released

the goats to cover the soldiers’ footprints. Some parts of the village were so dangerous that even working during the day was a risk,” he recalled.

Now serving as the deputy headman of Uukwandongo, Iyambo believes it was unfortunate that most of the original residents perished during the war.

“Dogs were left to feed themselves. I am just fortunate to be alive to tell the Uukwandongo story,” said Iyambo.

Though many original residents perished, Iyambo considers himself fortunate to have survived.

“The war silenced this place, but I am still here to tell Uukwandongo’s story,” he said.

Reflecting on Namibia’s hard-won independence, he expressed both pride and caution.

“We salute all those who sacrificed for this freedom. We also value the reconciliation policy of our Founding President, Dr. Sam Nujoma, which brought unity to our nation. But I want to remind our youth that independence did not come on a silver platter. It was paid for with blood and suffering. We must protect it,” he maintained.

Current situation

When asked about the challenges facing Uukwandongo today, Iyambo pointed to youth unemployment as the most pressing issue.

“Most of our young people are just at home with nothing to do. They rely on our pensions, which are not enough to support everyone. Others have turned to alcohol as a way of coping,” he explained.

He urged the government to provide opportunities for rural youth, especially those who lack skills or have dropped out of school. “We need training programmes, projects, or initiatives that can give our youth direction. Without support, they will remain trapped in poverty and hopelessness,” he said.