Between 1884 and 1908, German colonial conquest in South West Africa—today’s Namibia—produced one of the twentieth century’s first genocides. The 1904 war erupted not from Herero rebellion but from German aggression, when Lieutenant Ralph Zürn fired the first shots at Okahandja (known in Otjiherero as Ovita via Zürn), sparking an uprising rooted in land dispossession, forced labour, and racial humiliation. The OvaHerero’s armed response was an act of survival, a desperate attempt to defend their land, families, and dignity against relentless colonial exploitation.

Theodor Gotthilf Leutwein (1849–1921) governed German South West Africa for over a decade, constructing the system of colonial domination that laid the foundation for genocide. Through deceitful treaties, he stripped African leaders of sovereignty, land and livestock —claiming that “only when the native’s cattle are in our possession can he be truly controlled.”

The author of this analysis holds an original copy of Leutwein’s Elf Jahre Gouverneur in Deutsch-Südwestafrika, a rare primary source exposing his contradictions. In it, Leutwein denied genocidal intent yet justified coercive policies that created the conditions for mass atrocities. His system of labour and prison camps evolved directly into the concentration camps later formalized under von Trotha, making Leutwein the administrative precursor of genocide.

In 1894, he ordered the execution of Chief Andreas Lambert at Noasanabis near Gobabis, continuing the violence of his predecessor Kurt von François, who had in a Genocide-style massacred the Witbooi people at Hoornkrantz in 1893. Two years later, Leutwein attacked the Ovambanderu and executed by military-style firing squad their spiritual leader Chief Kahimemua Nguvauva in 1896, dismantling indigenous authority and society.

Upon his retirement in 1905, Theodor Leutwein was honourably discharged and awarded the Order of the Red Eagle, Second Class by Kaiser Wilhelm II in recognition of his colonial service in South West Africa, though his tenure equally involved violent suppression and the consolidation of oppressive German rule.

Although Leutwein later portrayed himself as a “moderate administrator,” his policies institutionalized racial domination. As historian Isabel Hull observed, “Leutwein habituated Germany to the logic of total destruction—Trotha merely completed what he began.”

Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha (1848–1920) replaced Theodor Leutwein after the 1904 OvaHerero uprising and brought with him a record of ruthless colonial warfare from East Africa and China. Rejecting negotiation, he launched a campaign of extermination, encircling the OvaHerero at the Battle of Waterberg in August 1904 and driving them into the Omaheke Desert. His Extermination Order at Ozombuzovindimba declared that every Herero, “with or without a gun,” would be shot, sparing neither women nor children. Thousands died from thirst, starvation, and bullets, while survivors were confined in concentration camps at Windhoek, Swakopmund, Lüderitz, Shark Island, and elsewhere—sites of forced labour, disease, and medical experiments that wiped out much of the remaining population.

After ordering the killing of Hendrik Witbooi at Vaalgras in October 1905, Trotha was recalled to Germany the following month. Despite global outrage, Kaiser Wilhelm II awarded him the Order of the Red Eagle, Second Class with Swords, for his “distinguished military service in the colonies.” Trotha died in 1920, unpunished and largely forgotten, yet his doctrine of racial extermination prefigured the genocidal ideology later perfected by the Nazi regime.

Samuel Maharero: The Human Face of Resistance

Samuel Katjiikumbua Maharero (c.1856–1923) embodied the opposite of German imperial cruelty. He turned to resistance when deception and dispossession became intolerable. When war broke out, Maharero united the OvaHerero clans and sought cooperation with other African leaders such as Hendrik Witbooi and Nehale lyaMbingana.

Unlike his German adversaries, Maharero fought with moral restraint. His orders forbade violence against missionaries, women, children, Boers, English, Damara and settlers. Despite Samuel Maharero’s explicit order forbidding the killing of Damara, the brutal policies of German commanders Theodor Leutwein and Lothar von Trotha led to devastating consequences. The British Blue Book (1918) reports that nearly 50% of the Damara population perished during the 1904–1908 conflict. Similarly, historian Horst Drechsler (1980) estimates that approximately 30% of the Damara were killed during the same period.

After the Ohamakari battle at Waterberg, he led his people through the Omaheke Desert in a strategic retreat that saved hundreds from annihilation. Exiled in Bechuanaland (now Botswana), he died in 1923. That same year, his remains were returned to Okahandja, where Red Flag Day has been held annually since 1924 to commemorate Ovaherero Genocide victims, honour his bravery, unity, and humanity.

Leutwein and von Trotha, born a year apart, embodied Europe’s imperial machinery of conquest, while their contemporary, Maharero, stood as its moral counterforce. Leutwein’s administrative rule laid the groundwork for domination, and Trotha’s extermination order brought it to its brutal climax. Driven by racial arrogance and imperial greed, both saw African lives as expendable, whereas Maharero transformed resistance into ethical defiance—his leadership symbolizing liberation against their oppression.

The year 1908 marked not only the end of Namibia’s brutal genocide, but also the beginning of continued oppression leading to apartheid. Sites such as Shark Island, Swakopmund, and Orumbo rua Katjombondi in Windhoek stand as grim reminders of the crimes of Leutwein and von Trotha, while also embodying the moral lessons that later shaped the United Nations’ human rights framework and its postwar vow of “Never Again.” Through the 1948 Genocide Convention, Namibia’s pursuit of reparative justice gains legitimacy via UN mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council, General Assembly, Permanent Forum on People of African Descent, and the International Court of Justice, elevating the OvaHerero and Nama cause from bilateral negotiation to global accountability—affirming that reparations and recognition are duties, not acts of charity.

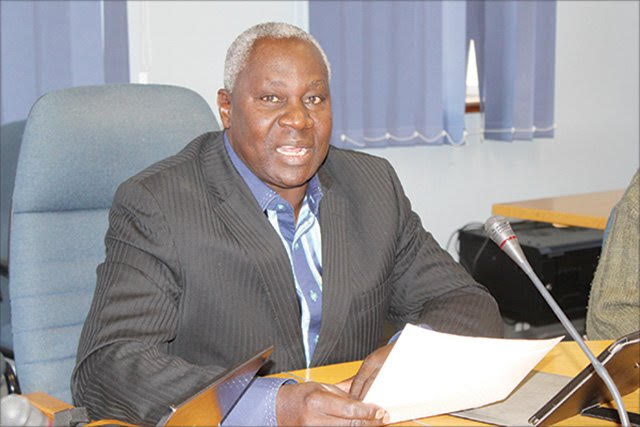

* Usutuaije Maamberua is a descendant of the victims of the Ovaherero/Nama Genocide. He is also a veteran of the Namibian liberation struggle. He writes in his own capacity.