Hilma Hashange

On 26 August 1966, the first battle, marking the start of Namibia’s armed liberation struggle, occurred at Omugulugwombashe village in the Uukwaluudhi area of the Omusati region.

On that day, the South African police launched a helicopter assault on a Swapo soldiers’ base.

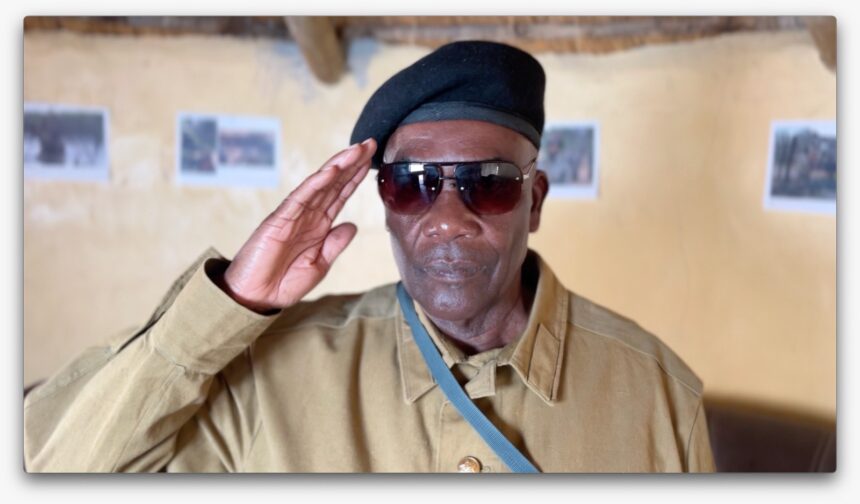

Immanuel Job, a resident of Onyaanya in the Oshikoto region, was only 10 years old at the time.

He vividly remembers how teachers were frequently arrested during school hours.

“We noticed that our country was not led by our own people but by the enemies because our teachers were being detained. We often missed school for days, and it became clear to us that something was wrong,” he recalled.

He also remembers a man named Eliaser Tuhadeleni, well known as Kaxumba KaNdola, who frequently visited their village, usually at night.

“I gradually got closer to him, and he eventually confided in me about the situation our country was facing. From that moment on, we questioned whether it was worth staying in a country where we couldn’t get an education. You couldn’t even walk freely, so we decided to leave the country and go into exile,” he narrated.

He said Swapo was initially formed to engage with the colonisers – not to wage war.

However, those in power refused to listen, and used every tactic to sow division.

“Namibians were separated into ethnic groups, and denied access to many resources. This led to the introduction of the contract labour system, where only men could work, often being separated from their families for years. Namibia was like hell because of colonialism,” he added.

Eight years after the battle at Omugulugwombashe, Job left what was then South-West Africa (now Namibia), and embarked on a journey to Angola.

“In 1974, Angola was nearing the end of its war, and the new Portuguese government allowed the Angolan political parties to form a united government. We crossed the border at Oshikango, entering Angola, where we encountered both the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola rebels and People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola forces,” he said.

Job and his group eventually met Swapo’s armed wing, the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (Plan).

He recalled figures like Wilbard Tashiya, known as Nakada, who was stationed in Angola, and responsible for training incoming soldiers.

“Initially, people from Namibia were trained in Zambia – but since it was far, Nakada was tasked with training us. However, it was later decided that we should proceed to Zambia for further training,” he said.

He was briefly trained at the Oshatotwa camp in Zambia in 1975 before being sent to Tanzania for specialised training.

“In Tanzania, I specialised in infantry and artillery. After completing our training, we didn’t return to Zambia due to the ongoing war. Instead, we went directly to Luanda, Angola, where we saw the aftermath of war, with bodies still lying in the streets,” he said.

The group then moved to Huambo, where they met the late Dimo Hamaambo, who was stationed in Angola.

They later continued to Cassinga before finally returning to Namibia.

Job recalled significant battles post-Omugulugwombashe, such as a 1977 ambush of enemy camps and a 1978 attack on South African soldiers at Erundu, led by Danger Ashipala. “We overran that post, and captured three enemy soldiers. There were even larger battles,” he recounted.

By 1984, Plan fighters were confident that freedom was imminent.

“The enemy attempted to destroy all towns near the Angolan border, using helicopters that were piloted by Israeli contractors. This signalled that the South African forces were losing strength, while the Plan was gaining momentum. We hit several enemy camps, starting in Xangongo then Cuvelai and finally Jamba,” he said.

He added that the Plan fighter concluded that the Cuito Cuanavale battle would be crucial in ending the conflict and securing Namibia’s independence.

“For Namibia’s freedom to become a reality, South Africa also had to gain independence. The two countries were interconnected. If the enemy left Namibia, they couldn’t remain in South Africa either. We predicted that they would eventually agree to a ceasefire to safeguard their possessions while negotiations took place,” he continued.

Despite the hard-won independence, Job feels some Namibians still do not appreciate the sacrifices made.

“Some people question why we celebrate Independence Day, calling it a waste of money. They forget that they can question it because they are free. Independence Day is not a Swapo day. It’s for all Namibians. Thanks to that day, every Namibian can now speak freely, and has rights. We must never downplay its significance, as it came at the cost of many lives,” he stressed. He urged all Namibians to continue building the country, and work towards economic stability.